Even though this is meant to be a triumphant scene where David is supposed to be the victor I can’t help but be drawn more to Goliath. I feel compassion for this beheaded man. I see the suffering and pain in his face which has far more humanity in it than the supposed victor who is parading his head on a stick.

Poussin is a master of extremely sophisticated visual rhythms. His many layers of rhythm, through mirroring and correspondences of form/color/symbol/shape do not only keep the eye engaged and moving through the picture but they also convey the narrative and deeper philosophical aspects of the story.

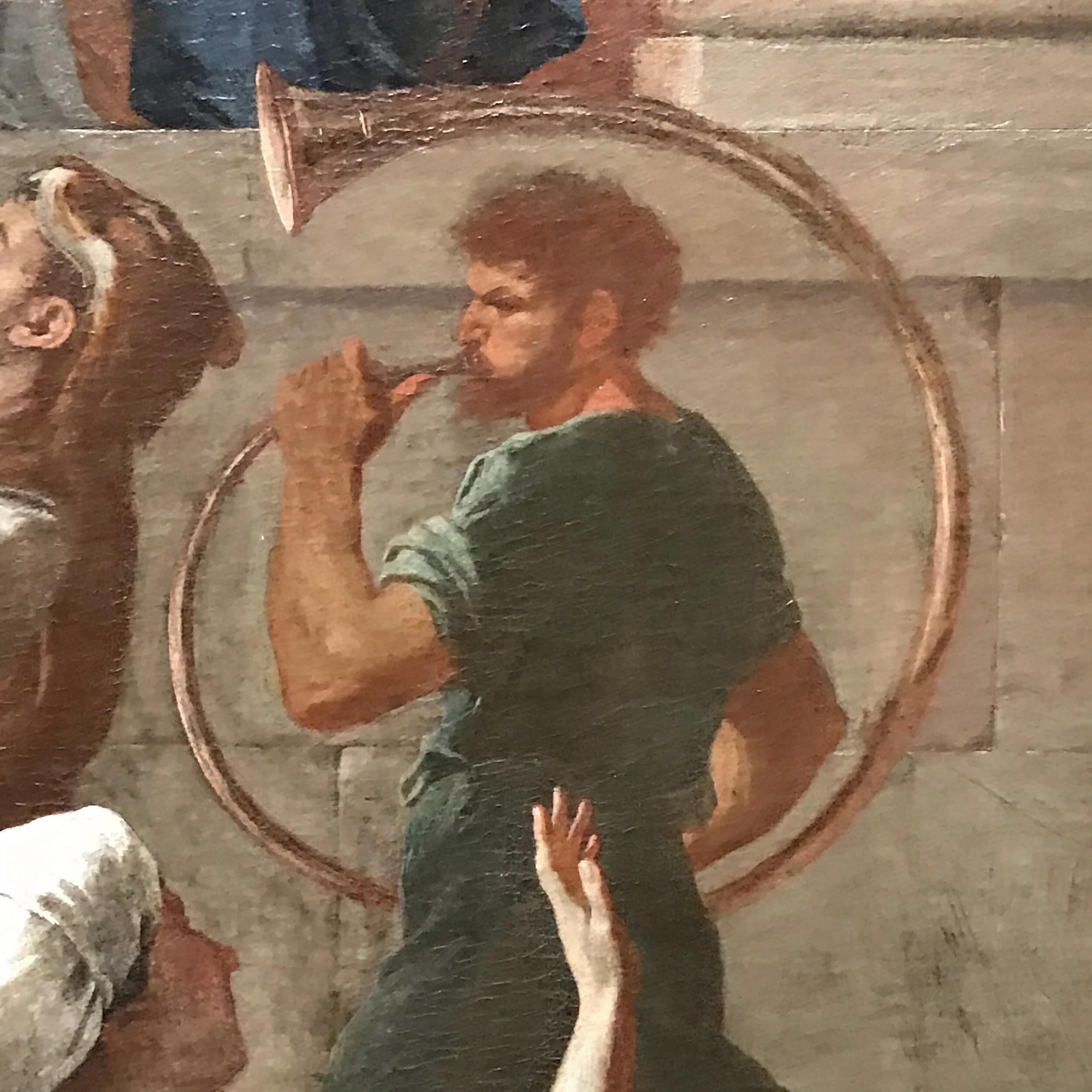

Almost exactly in the middle of the canvas is a soldier in the front of the procession blowing a circular horn. This portrait highlighted by the circular frame essentially puts a target on his head. This is the only circle in the painting and it’s right in the middle placing extra emphasis on it. In the foreground a seated woman’s highlighted arm is upraised in front of the horn player. The contrast between her light pink arm and his dark green tunic draws attention to him, her hand breaches the horn circle bringing even more attention to his encircled face. My eye keeps on darting back and forth between this figure’s profile and Goliath’s. Curiously enough they look almost exactly the same other than that Goliath’s head is much larger and the other man’s face is red full of life, breathing, blowing while the decapitated portrait is lifeless, green, grey and sullen.

They have the same nose and both have bushy red hair and beards. I view this resonance as a shared humanity. I don’t view Goliath as the “other”. It very well could have been the trumpet player who was beheaded on this day. Death could befall any of them, any of them could have been slain, but instead of celebrating the shared fragility of the human experience they have decided to parade the head of the “one who isn’t ‘Us’”.

In the Iliad Agamemnon was different than the rest of the Greeks because he had red hair. It was quite rare in the Mediterranean and the Middle East but in this painting 33 of the 45 figures are gingers (8 of the figure’s hair is covered so it could even be more). What surprises me is Poussin painted Goliath as a redhead also, he is not other, not of a vastly different tribe but from one that is actually incredibly similar.

This level of barbarity committed towards one of the same family, the family of the human race which is being celebrated is unnerving to witness. The figure leading the procession who is blowing the long horn is wearing a lion skin on his head and shoulders. One could easily read this as a mirroring of parading the exotic head/skin of the “other” but in this instance I see him as a half animal half human character and that he is leading the procession representing the bestial nature prevailing over human goodness. This is emphasized by the fact that the scene takes place in a muted tone ordered classical structure but is overwhelmed by horns and a parade of excited soldiers and onlookers.

There is great humanity in the painted details of this piece. A man on the right points to his forehead in a beautifully believable gesture. Yes this gesture can easily be read that he is telling the story of how Goliath was slain but also if you follow the line of where his finger and forehead lead they go exactly to Goliath’s forehead showing that they’re not so different after all and actually may be pretty close to the same.

Maybe what I find to be the most disturbing aspect is the mother in the lower right. She is wearing a light Terre Verte dress. This is the only area this color appears in the tightly orchestrated canvas which keeps bringing my attention back to her. She is joyous and enthusiastically pointing to the paraded head. When my eye finishes traveling through the parade of figures in the canvas it usually goes down to the bottom edge on the left and then goes straight to her. I see her pointing to this murder happily, showing her son, encouraging him to enjoy. His young eyes follow her pointing finger right to the carried human head on a stick, which leads me right back into the scene. My eye keeps on following this movement many times while I’m sitting here, which starts to feel very very depressing. This is this child’s education, this is what’s celebrated, this is what’s normal and my eye circling it over and over creates a sense of time and an endlessness of the cycle. It becomes this dark feeling that over and over again for thousands of years this behavior is being taught to subsequent generations and there’s no end in sight.

I become more and more interested in the woman in the top left of the canvas who’s face is hidden behind the column. I am hoping that she is the one figure who disapproves of this, hoping that her expression would convey to me that she is the true other, the only member of this scene that does not celebrate this act. It’s rare that I feel hope while looking at a painting but I do feel hope for this character, but I have a sneaking suspicion that it will be dashed, that like everyone else the blaring bestial intoxication of smiting the “enemy” has infected her also. And if that’s the case I will happily leave the scene through the sky window right above her head.